Guess-Free Minesweeper

Have you ever played Minesweeper? If you have, you’ve probably run into a situation where you’re forced to guess, hoping you’re not about to step on a mine and lose the game. What if I told you it was possible to make it so you never have to guess in a game of minesweeper?

In this post, I’ll explain how I made a minesweeper solver and how I used the solver to generate guess-free minefields.

For those unfamiliar, minesweeper is a deduction puzzle game. You play on a 2D grid of cells. Each cell may or may not have a mine in it. If you uncover a cell with a mine, you lose. If you uncover a cell with no mine, you can see how many neighboring cells have mines in them. As you uncover more cells, you gain more information about which cells may have mines. If you uncover all non-mine cells, you win and your friends can safely walk through the minefield!

If you know a cell has a mine under it, you can flag it to keep track of mines and make sure you don’t accidentally uncover a cell that you knew was a mine.

At the beginning of the game, one of the cells has a green "X". That cell is guaranteed to be mine-free so you can start the game without immediately losing. I call it the hint cell.

The best way to get an understanding of the game is to play it yourself. One popular site is https://minesweeper.online/. You can also play my less pretty version: https://quasarbright.github.io/minesweeper/. On both, you can click a cell to uncover it and right-click a cell to flag it.

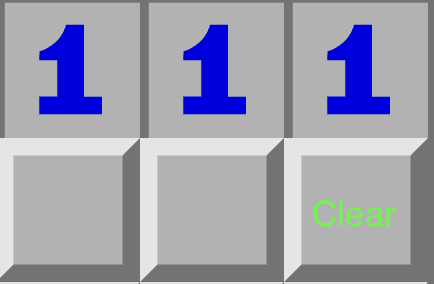

If you play for a while, you’ll start to develop these rules for quickly deducing whether to clear or flag a cell. For example, consider this scenario:

The 1 cell tells you there’s a mine in the center cell because there’s 1 mine neighboring it and only 1 cell that we haven’t uncovered. So that’s the only place where the mine can be. Here is another, similar sitiation:

The 2 cell tells you that there are mines in both the cells. In general, if you have an uncovered N cell with exactly N hidden neighbors, they must all be mines.

Conversely, if you have an uncovered N cell with N flagged cells around it, you can uncover the remaining neighboring cells. For example:

Assuming your flags are correct, you can safely uncover the un-flagged neighbors of the 3 cell. I call the 3 cell "satisfied" in this situation.

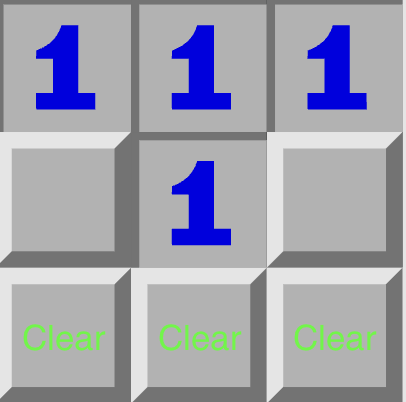

There are also some less obvious rules you can apply. Here is what I call the 1-1 rule:

From the leftmost 1 cell, you know there is one mine in either the first or second cell. The next 1 cell is like a superset of the leftmost one since it has the third neighbor as well as the first and second. It says there is 1 mine in either the first, second, or third cell. But we already know that the mine is in either the first or the second, so it can’t be in the third! This means we can clear the third cell.

Here is a similar situation:

Ignoring the corner 1-cells, from the top middle 1 cell, we know that either the middle left or middle right cells is a mine. This makes the center 1 cell redundant since its neighbors are a superset of the the top-middle 1 cell’s neighbors. Since the center 1 cell’s mine is either in the cell to its left or its right, it’s not in the 3 neighbor cells below it, so we can clear those.

In general, if a number cell’s hidden neighbors are a superset of another’s you can "subtract" the other cell’s information from the superset’s. We’ll make this more concrete later.

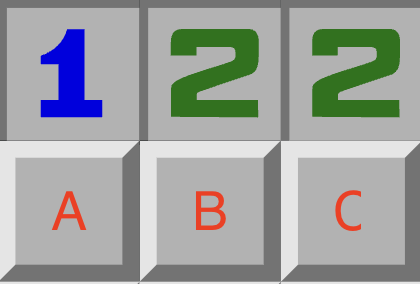

Another rule I use is what I call the 1-2 rule. Here is an example:

Let’s focus on the 1 and 2 cells. For a 2-cell with 3 hidden neighbors, we know that only one of those cells is mine-free. But its neighbors overlap in two places with the 1 cell’s, and the 1-cell only has 1 mine, so the rest of its neighbors are mine-free. This means at least one of the overlapping cells must be mine-free, so the rightmost neighbor (which isn’t one of the 1 cell’s neighbors) must be a mine.

There is a way to generalize this rule too, but we don’t have the language to nicely describe it yet.

One more thing we can take advantage of is the total remaining mine count. The game tells you how many mines are left, so you can use this information to eliminate certain possibilities. For example:

You know there is exactly one mine among the top cells and one among the left cells. There are two possibilities: One mine in the top left, or a mine in the top-right and another in the bottom-left. And we don’t know anything about the bottom-right. But if I told you that there is only 1 mine remaining in the whole minefield, it’d be impossible for there to be a mine in the top-right and bottom-left, so the mine must be in the top-left. And there must also not be a mine in the bottom-right!

With just these simple rules, you can get surprisingly far. You hardly ever need anything more.

If you’ve played a lot of minesweeper, you’ve probably developed a few rules like these and used them so many times that they’re like muscle memory, so automatic that you feel like a robot could do it. Hey, wait a minute!

Let’s make a solver using these rules. We’ll use something that I call "count-sets" to represent the information we can observe and deduce from looking at the minefield. A count-set stores a set of hidden cells and the exact number of mines among them. For example,

The 1-cell would give us a count-set with cells A,B and a mine count of 1. The middle 2-cell would give us a count-set with cells A,B,C and mine count 2. The rightmost 2-cell gives us a count-set with cells B,C and a mine count of 2.

If a count-set’s count is the same size as its set, like the rightmost 2-cell’s, we know they’re all mines and can flag them. Similarly, if a count-set’s count is 0, we know they’re all mine-free so we can clear them.

I call these count-sets certainties.

We write count-sets like this: \(1\{A,B\}\) is a count-set with 1 mine and cells \(\{A,B\}\).

Now we can talk about the superset rule, which is the generalization of the 1-1 rule I talked about before. If we have two count-sets and one’s set is a superset of the other’s, we can subtract the smaller count-set from the bigger one:

\[ NS,MT \rightarrow (N-M)(S-T),MT \]

Where \(T \subseteq S\)

We subtract the smaller count-set’s count and set from the bigger one. In my implementation, I threw away the original superset after refining it. Theoretically, we might miss some potential solutions by doing this, but in practice, it does fine. These rules don’t need to catch every solution anyway because we’re going to have a surefire backup in case we get stuck.

Why is this rule useful? Let’s think about possiblities. If we have the count-set \(2\{A,B,C,D\}\), there are \(\binom{4}{2} = 6\) possible configurations of mines that are consistent with that information. In general, the number of possible configurations for a count-set with \(N\) mines and a set of size \(|S|\) is \(\binom{|S|}{N}\). Certainties are certain because there is only one possibility: \(\binom{N}{N} = \binom{N}{0} = 1\). In the superset rule, we refine the superset by making it smaller, which reduces the number of possibilites. This is deduction!

Now we’re ready to talk about the 1-2 rule:

\[ NS,1T \rightarrow (N-1)(S-T),1(S \cap T),0(T-S) \]

Where \(|S \cap T| = 2\) and \(|S| = N+1\)

In english: If \(NS\) only has one non-mine among its cells and it overlaps two cells with a 1-count, those cells from \(S\) which don’t overlap with the 1-count must all be mines, the overlap must contain the 1-count’s mine, and the rest of the 1-count must not contain a mine. The intuition behind this is that at exactly one of the overlapping cells is a non-mine, therefore that’s the non-mine of \(NS\). So the rest of \(S\) must all be mines. And since we narrowed down where the 1-count’s mine is, we can refine that set and clear the rest of it.

Why is \((N-1)(S-T)\) all mines? The size \(|S-T| = |S|-|S \cap T| = |S|-2 = N-1\). So \((N-1)(S-T)\) is a certainty.

This rule could be generalized further, but it’s good enough in practice and already pretty confusing as-is.

When solving, we start out by creating count-sets from numbered cells. As a shortcut, we only need to consider numbered cells which are neighbors with hidden, unflagged cells. We’ll assume flagged cells have mines in them and subtract them from our count-sets. For example:

The 2 cell will contribute the count-set \(1\{A,B,C\}\). We have a 1-count because after accounting for the flagged cell, there’s only 1 mine left among A,B,C. And there’s no need to include the flagged cell in the count since we know it’s a mine.

We also add a count-set for the total remaining mine count. Its set contains all hidden, non-flagged cells, and its count is the total number of mines in the minefield minus the number of flags.

One more thing before we get to the main solver algorithm: These rules are pretty good, but they might miss some solutions. As a backup, we’ll make a brute-force solver.

This brute force solver will use our count-sets. here is the algorithmm:

|

cells = all hidden, unflagged cells |

|

for cell in cells: |

|

if assuming the cell is a mine leads to a contradiction: |

|

the cell is not a mine |

|

else if assuming it's not a mine leads to a contradiction: |

|

the cell is a mine |

This is like a SAT solver, but instead of trying to find one possible configuration of mines, we want to find out which cells must be a mine or not a mine.

To assume that a cell is a mine, we go through all count-sets that mention it, remove it from the set, and decrease its count by 1. To assume that a cell isn’t a mine, we do the same thing, but leave the count as-is.

To test whether an assumption leads to a contradiction, we try every possible assignment of remaining hidden, non-flagged cells as mine or non-mine. If we can find an assignment that is free of contradictions, the initial assumption is possible, so we can’t rule it out.

We have a contradiction when a count-set has a negative count or a count higher than its set size. This can only happen if we made a wrong assumption. As long we started with good information, if we make a single assumption about a cell being a mine and every possibility leads to a contradiction, that assumption must have been wrong, so the opposite must be true.

This algorithm is super slow since it tries a potentially exponential number of assignments, so we only use it when all else fails. And we break out whenever we learn the truth about a single cell since that new bit of information may allow us to make more progress with our more efficient hand-written rules.

Alright, now we’re finally ready for the main algorithm!

|

reveal the hint cell |

|

create count-sets from minefield |

|

loop: |

|

loop: |

|

loop: |

|

handle certainties |

|

loop: |

|

deduction |

|

loop: |

|

brute force |

loop means repeat the body over and over until we find a solution or stop making progress. If any step of the body results in a solved state, break out immediately.

handle certainties detects certainties present in our count-sets, flags and clears cells appropriately, and updates our count-sets according to the resulting minefield.

deduction applies the superset rule and the 1-2 rule to our count-sets.

brute force invokes our brute-force solver.

In english, we try handling certainties and applying our deduction rules over and over again until we reach a solution or get stuck. If we get stuck, try brute forcing until we learn something new, then go back to handling certainty and using our deduction rules and keep doing all this until we’re fully stuck or find a solution. We can get stuck if the minefield forces us to guess. Sometimes that’s unavoidable.

All right, now we have a solver. How do we use this to generate a guess-free minefield?

At a high level, what we do is start out with a random minefield. Then we solve as much as we can. If we get stuck, we move one of the mines that makes us stuck into a non-mine cell that we know nothing about. Then, we start over solving this new minefield from scratch, repeating until we can solve it all the way. If we wind up in a situation where we’re stuck and there’s nowhere to move the mines, like if the last two hidden cells are a 50-50, we start over with a new random minefield.

We can select one of the mines that makes us stuck by selecting a random cell from one of our (non-certain) count-sets, ignoring the total mines remaining count-set. And a cell that we know nothing about is a hidden cell that doesn’t appear in any of our count sets, ignoring the total mines remaining count-set.

In order for this to work, our selection of the hint cell needs to be deterministic. Otherwise, the solver might be able to solve the minefield from one hint-cell, but then the player gets a different hint-cell which could lead to them getting stuck. I generate the hint cell by sorting all cells by their distance from the center of the minefield and pick the first mine-free cell with a minimum count, which is almost always a zero-count.

One problem with this algorithm is that it tends to push the mines out towards the edges of the minefield. One way to mitigate this is instead of always pushing away when we get stuck, half of the time, we can pull a mine from the unknown cells into the cells we have some information about instead. But in practice, the effect is not really noticable, so this is unnecessary.

This guess-free generation strategy doesn’t actually require the solver to be perfect. For example, if you use a solver that only does handle certainties, you’d generate a minefield that only requires handle certainties in order to be solved. If we removed the brute force backup, we’d generate minefields that can be solved with just our deduction rules. This is nice because it means we can tweak the difficulty not only by changing the total number of mines, but also by changing the sophistication of our solver.

And there we have it! Now you’ll never have to guess in minesweeper again. Here is the source code for my implementation: https://github.com/quasarbright/minesweeper